Blue Ridge Parkway

Blue Ridge Parkway

History

The Blue Ridge Parkway is to National Parkways what the Great Smokies is to National Parks—a singular national treasure. There are parkways all around the country, but only four are managed as parkways by the National Park Service. At 469 miles, the Blue Ridge Parkway is both the longest parkway and the nation’s longest linear park (25 miles longer than another parkway, Natchez Trace). It’s also the nation’s most visited Park Service site.

The earliest parkways—among them are George Washington Memorial Parkway from Washington, DC, to Mount Vernon, VA—were built to mesh scenery in an early ideal of motoring as travel and recreation. That got its start with the creation of great urban parks by Frederick Law Olmsted, himself an early Parkway proponent.

The original idea for a Blue Ridge Parkway–style road originated as far back as 1909. By 1912, a privately-funded stretch of ridge-top toll road was constructed near Linville that later became part of the Parkway. By 1930, scenic roads between national parks became a topic. Then the Great Depression permitted the Public Works Administration to build roads to reduce unemployment. But the Parkway’s most immediate precedent was the 1931 start of construction on Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park. Later, that 105-mile, Depression-era relief project morphed into a park-to-park highway between Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks.

That’s when the battle over the Parkway’s location started. Virginia got the nod because of Shenandoah National Park. But Tennessee and North Carolina were left to duke it out for the Smoky Mountain connection, each claiming superior scenery.

Interior Secretary Harold Ickes sent Forestry Director Robert Marshall to weigh the two routes. Marshall reported that he could defend either choice, but favored North Carolina.

The political maneuvering of the route selection process climaxed at a September 18, 1934, hearing in Washington, DC. The Asheville Chamber of Commerce, wanting to sustain the city’s century-long tourist economy, hired a train to pack the hearing. The group appeared to be winning until Tennesseans revealed that Ickes’s selection committee had recommended the Tennessee route.

But on November 10, 1934, Ickes overruled his own selection committee and gave North Carolina the Parkway. Controversy continued and the Parkway barely became a reality on June 20, 1936, when a bill introduced by North Carolina congressman Robert Doughton passed the House, formally naming the road the Blue Ridge Parkway and transferring control to the National Park Service when completed.

Parkway construction had already started in North Carolina, south from the Virginia state line in September 1935. For decades, large uncompleted sections of road interrupted the route; by 1970, the road was complete, save for a short section at Grandfather Mountain (the National Park Service and the MacRae family, who owned Grandfather, had been debating ownership of the missing link for many years). In the 1950s, MacRae descendant Hugh Morton had built a tourist road to a “Mile-High Swinging Bridge” and the stage was set for stalemate. The Parkway wanted a higher road route to assure great views on public land. Morton wanted a lower route, to preserve the mountainside but also to protect the appeal of his tourist business. Finally, North Carolina citizens and the state sided with Morton.

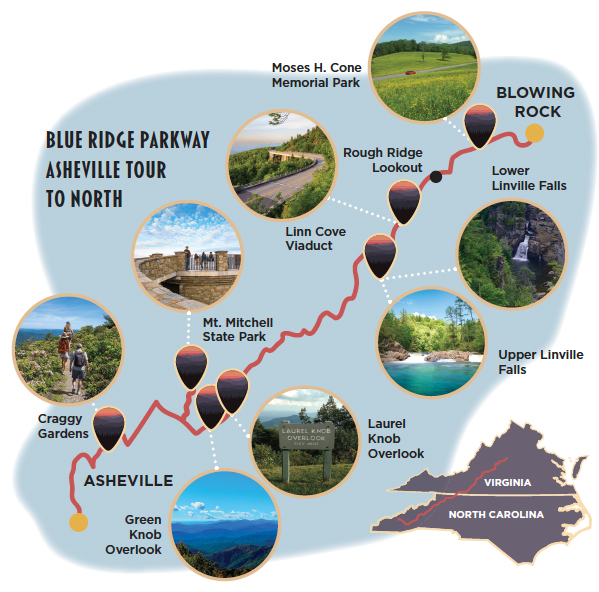

A “middle route” was chosen, the gap was closed, and the Parkway debuted as a seamless journey in 1987, two years after its 50th anniversary. The Grandfather Mountain portion of the Parkway contains not only the towering landmark mountain itself, but also the serpentine span of the Linn Cove Viaduct, one of North Carolina’s iconic travel attractions. This just may be the scenic high point of the entire Parkway experience.

At Milepost 19, visitors sit along the carefully-constructed wall at 20 Minute Cliff Overlook.

Why Visit

At almost half-a-thousand miles, the country’s longest national parkway stands alone as a National Park experience. Over that distance, “America’s most scenic road” offers a uniquely non-commercialized wander across the Appalachian crest. Many argue that Western North Carolina’s highest elevations are the Parkway’s most stirring sights.

Granted, there are overlooks, trails, and a long list of nationally significant natural sites and sights along the way, including important cultural and historical museums. Among them are the Blue Ridge Music Center, the Folk Art Center, and the Parkway’s main visitor center, the latter two in Asheville.

Who could forget that eastern America’s highest summits are reached just off the Parkway at Mount Mitchell State Park? Despite the iconic status of the Appalachian Trail, the grandeur of the Great Smokies, and New Hampshire’s White Mountains, only a hike across the peaks of the Black Mountains from Mount Mitchell bestows bragging rights for bagging five of the East’s top ten peaks—the first, second, fifth, seventh, and eighth—all within 10 miles.

That said, it may be the Parkway’s day-after-day driving experience of stunning scenery that sets it apart as a true tribute to the ideal of the American road trip. Despite competition from—and easy access to—adjacent resort areas, some early havens of Parkway roadside hospitality remain; there’s lodging at Pisgah Inn near Asheville and Peaks of Otter in Virginia, and classic dining at The Bluffs Restaurant in Doughton Park (named after the NC Congressman who helped vote the Parkway into being, then bought the land that later became his namesake park).

National forests and state parks (like Pisgah National Forest, first in the East, and Grandfather Mountain State Park) line the route too, offering campgrounds, trails, and almost-endless other options. It is easy to stretch a Parkway trip into a once-in-a-lifetime encounter with the vast rippled realm of the Southern Appalachians. Add Shenandoah’s 105 miles of Skyline Drive, and you get 600 miles of unbeatable views.

Learn more

Check out the NPS website for maps, closure alerts, road conditions, and more. nps.gov/blri