A Catalyst for Change

A Catalyst for Change: How Asheville is becoming world headquarters for climate science and ground zero in the quest to confront climate change

In 2010, Pakistan experienced epic flooding after unusually high rainfall during the monsoon season. Among the wreckage were mangled roads and bridges that left communities isolated from markets and life-saving services. As part of an ongoing effort to rehabilitate the road system, this past June, the Philippines-based Asian Development Bank announced a $197 million dollar loan to the Pakistani government to improve dozens of kilometers of roads and restore bridges. It’s a project far removed from North Carolina’s mountains, yet there’s a nearly boundless trail of data that will link the fresh pavement in Hyderabad to Western North Carolina.

Before financiers in Manila approved the loan, they considered a range of lending risks, among them the impact of climate change in a region particularly vulnerable to climate fluctuations and extreme weatherevents. For help, they turned to John Firth, CEO of the UK-based Acclimatise, which has an office in Asheville.

Acclimatise creates software to help lenders zero in on risks and suggest questions that developers should ask to increase project resilience, including building roads that can withstand devastating monsoons. For the user, the software appears relatively simple, yet Firth points out that “sitting behind the application are millions and millions and millions of data points.”

That actually may be an understatement. The software is backed by 26 petabytes of weather and climate data. Consider this: If you counted one byte per second, it would take nearly 40 million years to count the total bytes in just one petabyte.

That enormous stockpile of digits is one of the central factors behind Acclimatise’s decision to base its North American headquarters in Asheville, just a stone’s throw from the federal building where the entire world’s climactic data—26 petabytes worth plus 275 years of paper records—is stored. Another was to be side by side with one of the globe’s largest assemblage of climate scientists and researchers addressing one of the world’s most complex problems: climate change. And it’s why many boosters of an emerging climate data industry, such as Firth, are predicting Asheville will become an international hub of climate science.

“I don’t want to sound ridiculous, but I believe in years to come we’ll be talking about Asheville as a global solutions lab for people who are trying to understand what a changing climate means,” says Firth. “This is one of the few moments in life when you look at something and think, this is an opportunity that can be sky high.”

A FOUNDATION IN CLIMATE SCIENCE

Mike Tanner, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Center for Weather and Climate, is the curator of the massive aggregation of oceanic, geophysical, coastal, and atmospheric data housed in Asheville’s federal building. “We’re one of Asheville’s best kept secrets,” says Tanner, who took the helm of the data center seven years ago.

However, the trove of data he manages isn’t confidential. In addition to preserving and monitoring the storehouse of information, his agency also has a public duty to share it. Anyone who tunes into the local news has been a recipient. When the weatherperson quotes the high temperature in Boston or Bend, that information is sourced from Tanner’s archives.

He’s also a colleague to around 500 experts including scientists, programmers, communicators, and designers. While some of the science they generate may be impenetrable to a novice, Tanner’s mission is to make it accessible.

“The most important job for us is to take an incredibly complex scientific idea and communicate it to folks who can use it to make decisions in business or in Congress,” says Tanner. “For most people, their last science class was as a freshman in college. We need to be able to communicate so they can understand.”

While the work of Tanner’s agency is supported by state-of-the-art computing, the agency actually has humble roots in a pre-digital age.

Credit belongs to President Ulysses S. Grant, who in 1870 signed into law a resolution to create a national weather service to gather and record climate observations. And in order to keep the growing storehouse of data on temperature, wind speed, and humidity, the federal government organized the National Weather Records Center in New Orleans in 1934.

The responsibility to collect and organize weather data landed in Asheville in 1951. Uncle Sam had purchased the Grove Arcade in downtown—then the largest building in the region—nine years prior to house the U.S. General Accounting Office’s Postal Accounts Division. So as the Cold War was underway and the U.S. government sought to move its weather archives to a more under-the-radar and non-flood prone location, Asheville fit the bill. It was within a day’s train ride from D.C., had a space large enough to house the growing archive, and a trained federal workforce already in place.

By 1956, Brig. General Thomas S. Moorman, commander of the Air Weather Service declared to the Asheville Citizen that “Asheville is the world center of climatology.” His comment was made as thegovernment agency entered the digital age. No longer would Asheville stockpile punch cards, microfilm, ledgers, and charts in file cabinets and on shelves. Moorman and other Asheville dignitaries were celebrating the delivery of the state-of-the-art IBM 705, what the newspaper reported to be one of the world’s largest “electronic brains.” The mass of machinery included 23 separate units, so large, they had to be lifted into place in the Grove Arcade by a five-story-tall crane.

Known as the “tape ape” for its remarkable ability to store a file cabinet of data on a single reel of tape, the computer was so fast for the time, in fact, that if it were fed the novel Gone with the Wind it could complete the volume in three and a half minutes.

The mass of raw data collected could also be divided and crunched into useful and practical information to plot sea-lanes, predict energy demand and soda pop consumption, and in the Cold War era, plan strategies to avoid fallout from atomic warfare.

The information was also of assistance to climatologists—scientists who study how observations of weather information change over a long period of time and how those trends impact daily lives.

The application of data to better understand climate trends has, in fact, been on scientists’ radar for decades. In 1960, the director of the National Weather Record Center, Roy L. Fox, observed in the Asheville Citizens that the world was warming. Three decades later, an article by journalist Clarke Morrison reporting about the weather agency took the idea a step further, noting that the “question of whether the Earth is warming will probably be answered in Asheville.”

It turns out Morrison was right. At that time in the early ’90s, the climate data agency was building a baseline of global information for the specific study of climate change.

Fast forward to January 2015, and following several changes in scope and name, the agency based in Asheville was reorganized as the headquarters of the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), which includes Tanner’s Center for Weather and Climate and the Center for Coasts, Oceans, and Geophysics.

While a warming climate is conclusive, the impact of climate change and how communities in the Carolina mountains or residents of Pakistan adapt is another question entirely. Which is exactly why experts such as Firth and Tanner are so bullish on the rise of Asheville as a center of climate science and services.

“We, as a society, are more weather- and climate-conscious than ever. And because of that, folks are making decisions on this type of information,” explains Tanner.

Now, more than half a century after the Grove Arcade was selected to stockpile mounds of weather records, interest in Asheville’s wealth of climate data is seeing a revival, spurring a potentially promising industry to solve climate-related problems.

MOBILIZING GREAT THINKERS

This past March, North Carolina entrepreneur and philanthropist Mack Pearsall hosted the opening of his venture, The Collider, in the sleekly renovated fourth floor of the Wells Fargo building overlooking Asheville’s Pritchard Park.

The nonprofit enterprise is focused on the commercialization of climate data and serves as both a co-working space and catalyst for collaboration around products and services dedicated to climate change adaptation.

Pearsall is hoping The Collider will help bring to the mountains a share of the estimated $300 billion industry centered on climate change innovation and resilience that includes building climate-resistant roads in Pakistan or designing crops that can tolerate weather extremes in Iowa.

Pearsall became interested in understanding more about rising sea levels a decade ago. “I got to see more broadly and unmistakably the risk and clear and present danger of climate change,” he explained to the crowd of boosters at the opening, including U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx.

Among The Collider’s nearly two dozen current member businesses is Firth’s Acclimatise and UNC Asheville’s cutting-edge National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center (NEMAC).

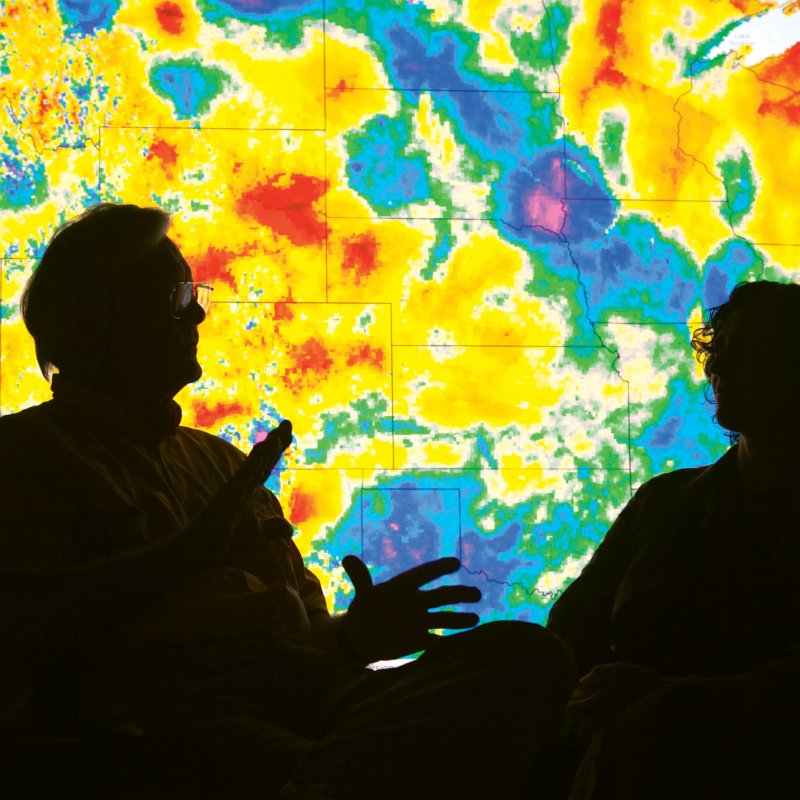

“Climate data by itself is not useful; it takes people with the expertise of discovering what the data means and the ability to visualize it so people can understand it,” says Jim Fox, NEMAC’s director since 2005.

And that’s just it: The Collider is amassing under one roof the expertise and innovation required to develop a fledgling industry that will lead the way in responding and adapting to climate change.

As of August, Pearsall selected James McMahon to serve as The Collider’s CEO. Having studied physics at Harvard University and atmospheric chemistry in relation to polar ozone depletion at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and following a 10-year career working in technology management for Coca-Cola in Atlanta, McMahon brings to the job both scientific and business acumen. He also served as a senior advisor for the head of what is now NCEI for six years prior to stepping into his new role.

“It’s hard to find people who have business and scientific experience,” he says, “but I’m one of those unusual types who is interested in both. In the past, I’ve positioned myself as unfocused, but it turns out that all of my background leads up to this moment.”

While Pearsall’s vision included developing a world-class space for collaboration at The Collider, McMahon brings to the table the ability to connect market needs with scientists, programmers, engineers, and entrepreneurs who can find marketable solutions.

“My job is to create clarity in the climate services industry about who does what and the chain of how data becomes information and information becomes insight that can then be acted upon,” says McMahon.

For instance, financial firms such as the Asian Development Bank will increasingly consider climate change among their risks and will need gobs of data to assess it. Health care companies will need climate data in order to aim their research at diseases, such as the Zika virus, impacted by changing climate conditions.

The potential opportunities are exactly what convinced Firth and many other climate-related companies and organizations to base their work in Asheville.

“People are always amazed to learn that all of the world’s climate data is stored in downtown Asheville and that some of the world’s leading climatologists live here,” says McMahon. “We have a tremendous resource here that is largely untapped.”

A PATH TO ECONOMIC PROSPERITY

Establishing Asheville as an international hub for climate science isn’t a job left solely to The Collider and its member businesses. Clark Duncan of the Economic Development Coalition for Asheville-Buncombe County is providing support, and confirms that the climate and environmental data industry has evolved into one of the cornerstones of this area’s economic growth strategy.

“This is a really unique opportunity that we can own,” says Duncan. “We think Asheville is well positioned to see the industry grow here. We have the talent, the academic and industry partnerships, and the federal investment.”

While the Beer City slogan is safe for now, it’s not a stretch that Asheville could one day be known for more than just IPAs.

Climate City may not have the same buzz, but the rise of the high-tech industry around data and climate science will help address not just global challenges, but also one of Asheville’s most pressing problems: providing jobs that pay well.

Career opportunities with a decent salary have seemingly been scarce in Asheville, but launching an emerging industry based in technology could change that.

In fact, Duncan’s colleague Matt Popowski says that high-tech companies are already looking to attract talent. “People say you have to bring your job to Asheville, but we’re finding that’s not true,” says Popowski, who established a new job board hosted by the EDC.

But don’t expect job announcements in the hundreds in the emerging climate data sector. The sweet spot, says Duncan, are firms in the range of two to 20 employees, such as Locus Technologies, a Silicon Valley-based environmental information management software company that opened an office in Biltmore Park in 2011.

While there may be not be a template for developing a city-centered high-tech industry, Duncan cites Norman, Oklahoma, as an example of a small city that has capitalized on a fledgling sector. In its case, it’s a hub for weather research and radar-related enterprises. Like Norman, Asheville is home to a potent combination of unique assets and experts, Duncan says.

Although Asheville doesn’t have a major research university from which to source highly talented labor, the presence of NEMAC, climate-relevant undergrad programs at UNC Asheville, and locally basedorganizations such as the American Association of State Climatologists and North Carolina State University’s Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites have aided in establishing ties to academia.

Duncan explains that in addition to his role marketing Asheville to potential firms, he’s also tasked with establishing an entrepreneurial infrastructure that will help support new businesses, including the organization of a mentor program for entrepreneurs, job networks to match businesses with tech-savvy talent, and funding sources for new companies.

Of course, workers suitable for the industry are already coming to Asheville, job openings or not. Duncan says that Asheville is attracting new younger residents at a rate of five millennials for every baby boomer.

And not only is access to masses of climate data and top experts a draw, but Fox of NEMAC says that the high quality of life in the area will play a central role in attracting creative and accomplished climate scientists and entrepreneurs. In fact, it’s what attracted Fox, a Hickory native and military brat, to Asheville after a lucrative career in the offshore oil industry.

Fox believes that a big part of his organization’s mission is “building capacity” to mature a data-driven climate industry in Asheville. NEMAC has hosted 120 student interns since its inception, many of whom are currently working in the climate industry.

One of them is Jeff Hicks. After graduating from UNC Asheville in 2008, Hicks stayed on and eventually launched his own business headquartered at The Collider. Fernleaf Interactive capitalizes on Hicks’ data visualization skills gathered on the job with NEMAC, and helps communities, businesses, and governments prepare for the impacts of climate change. “Ultimately we’re doing the work for people who need to make decisions [that come] with a huge amount of uncertainty,” explains Hicks.

Which is exactly why so many people feel that the climate services industry is on the cusp of a growth spurt, with ground zero in Western North Carolina.

“There are a lot of people who are taking the risks of climate change incredibly seriously,” says Firth of Acclimatise, which means Asheville’s abundance of climate data and knowledge won’t be a secret, butrather a world-class resource in sorting out the challenges of climate change.

“This place could be globally significant,” he says. “Not only can we solve major world problems and issues right here, but we can also make it into a massive opportunity for this community. To have gotten in on this early stage and to have this shared vision is just amazing. That’s what excites me about Asheville.”

Climate Cluster: Get to know the major players in climatology that call Asheville home

American Association of State Climatologists

The AASC, which moved its headquarters to Asheville a year ago, is the professional organization of the nation’s state and regional government climatologists. www.stateclimate.org

14th Weather Squadron Stationed in Asheville’s federal building, this Air Force unit serves all of the U.S. armed forces and the intelligence community. Its official mission is “to collect, protect, and exploit authoritative climate data to optimize military and intelligence operations and planning.” Facebook: 14th Weather Squadron

The Collider

Opened earlier this year, this nonprofit co-working center fosters collaborations among climate scientists, educational institutions, government agencies, and businesses. Member businesses include the companies Global Science & Technology Inc., which produces scientific visualizations, weather applications, and other advanced products, and Acclimatise, a British-based climate change consulting firm. www.thecollider.org

Cooperative Institute for Climate and Satellites

A research consortium founded by the University of Maryland College Park and North Carolina State University, CICS partners with the National Centers for Environmental Information to research climate shifts and train the next generation of climatologists. www.cicsnc.org

National Centers for Environmental Information

A division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NCEI is the main tenant in Asheville’s federal building and houses the world’s largest collection of climate and weather data. Within NCEI is the Center for Weather and Climate and the Center for Coasts, Oceans, and Geophysics. www.ncei.noaa.gov

National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center

Part of UNC Asheville and based at The Collider, NEMAC specializes in multimedia science communications such as visualizations of climate and weather, forest ecology, natural hazards, and land use. www.nemac.unca.edu